You see fire, they said, but fire is just an expression of one form of oxidation. What’s important is not what you can see, but what you can’t.

Elizabeth Povinelli (2017: 506)

Yet if in any country a forest was destroyed, I do not believe nearly so many species of animals would perish as would here, from the destruction of the kelp.

Charles Darwin (1839: 391)

T

he partially exposed building foundations of the Hercules Powder Company’s facilities at Gunpowder Point, Chula Vista, California, are all that remain of a once-vast complex. They peek out of the marshy lowlands where the munitions manufacturer built a specialized operation to process kelp extracted from the Pacific Ocean. Hercules burned the removed kelp to gather substances needed in their chemical products. Scattered pages online show these quasi-brutalist ruins still hiding in plain sight, though seemingly sinking (or someday soon to be under the tides).

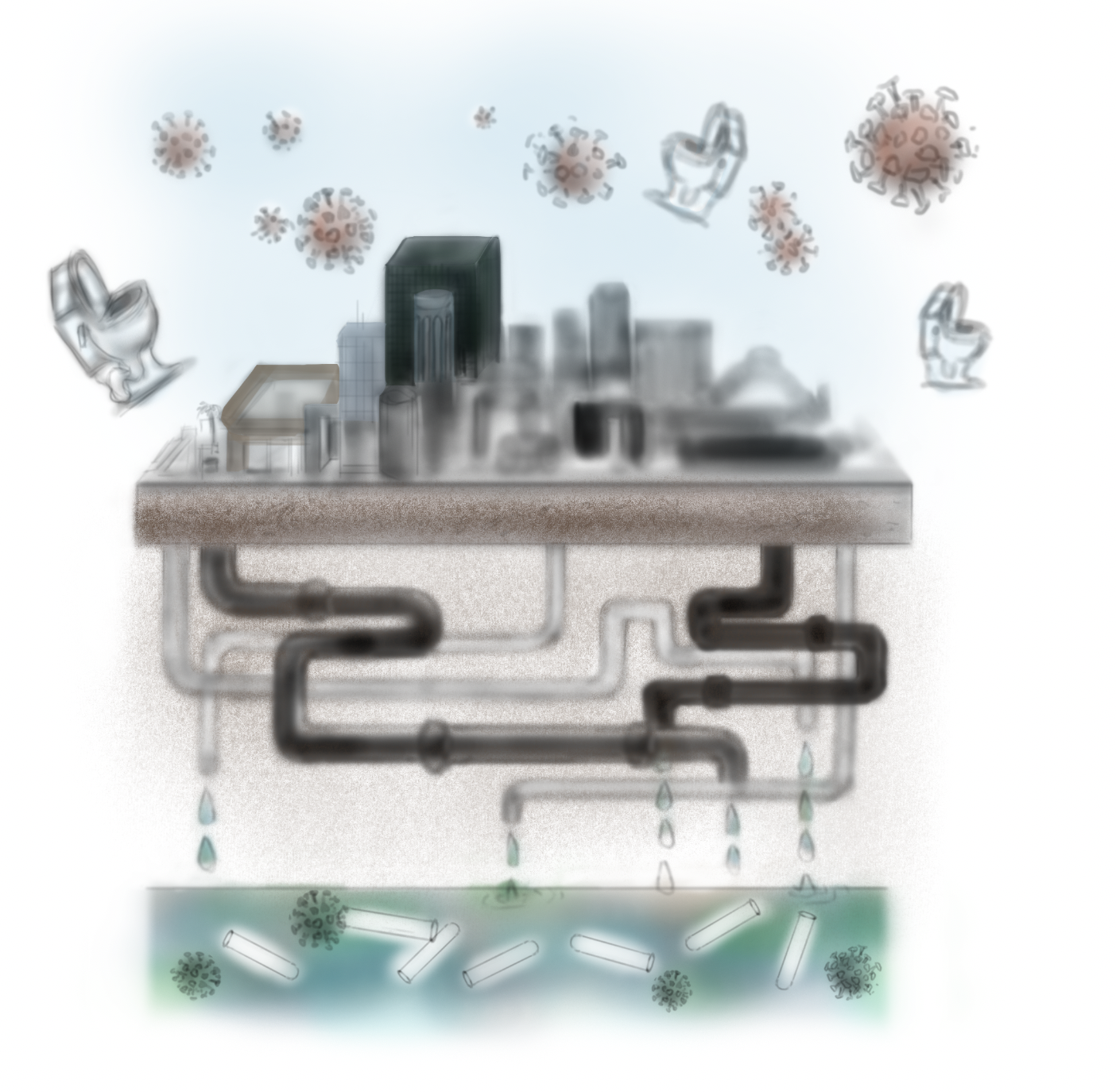

Why visit these ruins? What could sight reveal, first hand, that secondary sources could not? These questions intrigue me because of an enveloping condition of explosivity: the latent potential to ignite atmospheres in and around bodies. When visiting toxic landscapes that were sacrificed for the production of such explosivity, what can be seen is oftentimes much less than what cannot. Yet, as Elizabeth Povinelli suggests in the epigraph above, the invisible portion of the chemistry is key to thinking about new human-nature relationships. As she adds: “Between the rising tides and chemical burns, our bodies are stew pots cooking up a new form of posthuman politics with new forms of posthuman corporealities” (2017: 509). The Hercules ruins indirectly stand in for past violent chemical relationships that produced explosivity (see also Romero et al., 2017). However, deriving much from this site by direct in-person sensing or from a digital map can be challenging.

Words are supposed to help us with sight and meaning, as one attempts to envision what can’t be immediately apprehended. But the word “kelp,” as I’ll clarify further, was originally coined to name the diverse sea vegetation meant to be collected together and consumed in flames, and made into indistinguishable ash. Quixotically, in Chula Vista one might come to piece together a larger story of what is happening to kelp, which is—as we learn from climate reporting—disappearing. How is kelp disappearing? A purple sea urchin, “the cockroach of the seas,” thrives in warming climates and consumes the kelp, leaving formerly lush tidal zones barren of any lifeforms (Filbee-Dexter and Wernberg, 2018). Little could Darwin have imagined how prophetic his passing remark about the destruction of kelp would be (see epigraph above); he attributed to kelp forests the existence of entire food pathways leading all the way to the indigenous people of Tierra del Fuego — “savage,” “the miserable lord of this miserable land” to him (1839: 392), although they likely knew more about the so-called kelp’s fragility than he did.

The boom in explosives manufacturing

Between the mid-1860s and the end of World War I, companies like the Hercules Powder Company and others, such as Judson and Giant, revolutionized explosives with innovative mixtures and detonation technologies that could minimize inputs, maximize explosive power, and allow for manageable transport and handling (often at the blood-price of indentured Chinese laborers, killed in countless accidents). The manufacturers clustered in what could be remembered as the Silicon Valley of explosives, an explosives belt that spread across Northern California from San Francisco’s outside lands, gradually moving across to the tidal edges of Contra Costa County, as growing cities continually banned the “noxious uses” of these factories that frequently blew up (Walker, 2004). Seth Lunine explains that “California possessed only seven of the nation’s twenty-two dynamite manufacturers in 1880, yet these California companies accounted for about ninety percent of all capital investment and over seventy percent of aggregate national output” (2013: 101).

But the ruins of Hercules, located in the southern part of California territory, reveal a vital element in the production of explosives: potash (a potassium compound). The Hercules plant in Chula Vista was a specialized operation – a spin-off from the north, built for cooking kelp to extract potassium for gunpowder and acetone for cordite, a smokeless propellant used in the detonation of shells. Other derivatives included solvents for airplanes and an ingredient for aspirin, used at the end of World War I to treat soldiers during the Spanish flu epidemic (Williams, 1920: 33).

Germany produced most of the mineral potash around the world in 1914. When the war closed off this supply line, it created the opportunity for companies like Hercules to capitalize on California’s kelp that had formerly been too expensive to meticulously process. In a startling essay with an engrossing title, “Seaweed for War: California's World War I Kelp Industry,” Peter Neushul says that “although short-lived, California's World War I kelp industry was the largest ever created in the United States for the processing of plants from the ocean” (1989: 561)—and the Hercules facility in Chula Vista was the biggest of them all.

During World War I, 1,500 people worked at Gunpowder Point, which operated day and night. At a distance between keyboard and site, it’s hard to reconcile the handful of images that show the vastness of the plant in the past with the mellow recreational landscape of the present. Before a science center and hiking trails came to occupy this location, someone planted tomatoes commercially, leading a guerrilla filmmaker to storm these very same fields (unpermitted) to film a scene for the 1978 cult classic Attack of the Killer Tomatoes.

Neushul notes: “Between 1915 and 1917, Hercules was the largest foreign manufacturer of cordite for the British, delivering a total of 23,000 tons” (1989: 562). Hercules commissioned three specialized ships built to extract the kelp from the ocean, and used seven barges to constantly transfer matter from the harvesters to the shore. The harvester ships had what resembled stadium seating on the hulls to drag the kelp from the water. 200 wooden tanks for 50,000 gallons of chemicals each stood in orderly rows that contrasted with the raggedness of the shoreline. But although the kelp operation was massive, it declined just as rapidly as it had appeared (Schoenherr, 2014).

Very little of what I just described above can be deduced from visiting these ruins, however. Even if thematically tied through the environmental history of kelp, the question remains as to whether the declining kelp can be saved by using knowledge drawn from a visual appreciation of this landscape. But there are insights, particularly from landscape studies, geography, and the attunements literature, that compel one to go and get in touch with an archival uniqueness that would be impossible through any other media. The still-visible ruins and the disappearing kelp, together, can illustrate the long trajectory of the chemical relationships taking place—rooted in militarization (Belcher et al., 2019)—linking us to the present state of a warming climate and its consequences.

What one word ignites

The word kelp (Middle English) has a surprising and revealing history. It was first coined by potash makers in the 16th century, used at that time for glass and soap-making. According to the OED, kelp first referred to seaweeds “burnt for the sake of the substances found in the ashes.” Kelp was a substitute, in fact, for a decline in wood ash —which is itself a revealing insight into the politics of naming and extinction—to conjure from nature a partial remedy to losses, along strictly human priorities. Kelp is a word meant to conjure chemicals from disparate reactions in several distinct species, and to appear to human vision as one substance. Furthermore, kelp is a term that exists to force nature to solve commodity crises. What we call kelp is a confusing distortion. This distortion also makes the present disappearance of “kelp” all the more difficult to resolve, because these enormously diverse coastal ecosystems, made up of various species, have long been named as flammable.

In turn, I suggest that we can think of California's fragile kelp forests—at times mere splotches on the surface of the water, just underneath the register of visibility, in the background of the idyllic postcard view—as part of a continuum of explosivity. Although seemingly passing through several disparate and distinct crises—from their weaponized past to recent times when kelp was proposed as a potential green energy fuel, and then to a borderline casualty of global warming (a heartbreaking and ironic reversal in the present)—these crises can all be related back to naming seaweeds for their conflagration.

The kelp decline portends to eliminate a vital “carbon sink” for no less than the survival of humans and many more species on this planet. The kelp forest and its extinction are interconnected by seemingly conflicting kinds of extractivism: in short, the activity to retrieve and burn substances that add carbon to the atmosphere, and the farming that exploits photosynthesis to remove that carbon. Regimes of greening the environment continue to treat photosynthesis in plants like kelp as a base environmental service to compensate for human follies. This is what Jane Bennett might single out as a negation of the “thing-power” in non-human species (Bennett, 2004). Even when seemingly fighting different wars—against armies or against climate change—these various applications of sea plants subsume photosynthesis to human subjectivity. This is done to balance a spreadsheet of a certain amount of carbon in the environment, defeated by global warming and foreclosing on new chemical possibilities. The Hercules ruins are also the ruins of a very elemental reaction prefigured by the needs of explosivity. The ordinariness of this chemical reaction, produced with what was back then a quite plentiful and freely plundered resource—as free as oxygen itself—nevertheless left us with this enduring carcass of an imagined future of permanent war. Why?

Because as any improvised bombmaker can explain, explosives are nothing but everyday chemicals and compounds, even when symphonically composed into extremely sensitive and complex assemblages. Visiting the Hercules ruins can be a way to perceive the materialization of the latent explosivity in the natures around us. Preventing such combustion, and possibly saving our species, could mean doing away with “kelp” as a combustion-related term, lest we want to restore these sea forests back to some condition of potential exploitation for wars yet to come. The ruins of the Hercules Powder Company could be treated as an archive in the landscape, one that contains the codes with which to continually revitalize violence that begins with elemental natures—or a dire warning of what to prevent. The ruins are sarcophagi that can “re-kelpify” the seaweeds if humanity is not vigilant. And if environmental remediation succeeds, we are still committed to the same chemical relationships that advanced wars, and that can be weaponized once again.

Acknowledgements: I’d like to express my gratitude to Caren Kaplan, Tess Lea, Gabi Kirk, and the editors at Society and Space for all of their patience and thoughts in developing this piece. My thanks as well to the University of California Humanities Research Institute and the Civil War research group for opportunities to discuss this work together. I especially want to thank Diana Pardo Pedraza who contributed research and has been an invaluable colleague sharing exploratory thoughts throughout, and to Bryan Finoki for his comments on this piece as well.

Other essays from this forum include:

Editors' Letter. Everyday Militarisms: Hidden in Plain Sight/Site, Caren Kaplan, Gabi Kirk, and Tess Lea.

Residue and Restoration: Hiking through Militarized Landscapes, Toby Beauchamp

The Militarized Campus Arboretum, Gabi Kirk and Robert Moeller

Selfies and Submarines: The Social Media of Military Recruitment, Stella Maynard

On Landmines and Suspicion: How (not) to Walk Explosive Fields, Diana Pardo Pedraza

References:

Belcher O, Bigger P, Neimark B, and Kennelly C (2019) Hidden carbon costs of the "everywhere war": logistics, geopolitical ecology, and the carbon boot‐print of the US military. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers. Epub ahead of print 19 June 2019. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/tran.12319

Bennett J (2004) The force of things: steps toward an ecology of matter. Political Theory 32(3): 347–372.

Darwin C (1839) The Voyage of the Beagle. London: Smith Elder and Company.

Filbee-Dexter K and Wernberg T (2018) Rise of turfs: a new battlefront for globally declining kelp forests. BioScience 68(2): 64–76.

Lunine SR (2013) Iron, Oil, and Emeryville: Resource Industrialization and Metropolitan Expansion in the San Francisco Bay Area, 1850-1900. PhD Dissertation, University of California, Berkeley, United States.

Neushul P (1989) Seaweed for war: California’s World War I kelp industry. Technology and Culture 30(3): 561–583.

Povinelli EA (2017) Fires, fogs, winds. Cultural Anthropology 32(4): 504–513.

Romero AM, Guthman J, Galt RE, Huber M, Mansfield B, and Sawyer S (2017) Chemical geographies. GeoHumanities 3(1): 158–177.

Schoenherr S (2014) Gunpowder Point History - South Bay Historical Society. Available at: http://sunnycv.com/history/exhibits/gunpowder.html (accessed 4 October 2019).

Walker R (2004) Industry builds out the city: the suburbanization of manufacturing in the San Francisco Bay Area, 1850-1940. In: Lewis RD (ed) Manufacturing Suburbs: Building Work and Home on the Metropolitan Fringe. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, pp. 92–123.

Williams WB (1920) History of the Manufacture of Explosives for the World War, 1917-1918. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Javier Arbona is an Assistant Professor with appointments in the departments of American Studies and Design, and an affiliate of the graduate groups in Cultural Studies and Geography at the University of California, Davis, where he co-leads the Critical Militarization, Security, and Policing Studies research cluster. He regularly collaborates with the Demilit experimental landscape collective.